Mark Ryden, Debutante (1998)

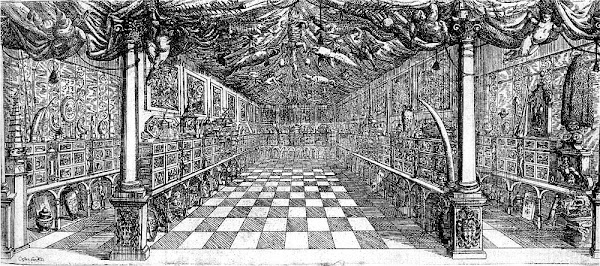

Vicent Levinus, Wondertooneel der Nature (t. I, 1706, t. II, 1715)

"IN 1706 THE DUTCH MERCHANT Levin Vincent published a book titled Wondertoonel der Nature that features etched images of his collection, which included preserved and taxidermied animals, skeletons, mysterious fossils, fantastic corals, and beautiful seashells. Beginning in the 1500s, Europeans began assembling individual collections of natural and man-made objects and filling their “cabinets of curiosities” with specimens that gave them a sense of wonder about the world and satisfied their fascination with oddities. Wonder chambers, Wunderkammen, like those of Levin Vincent evolved over the centuries into modern museums.

When I walk around the halls of a museum, I have experiences like those of learning about the world I had in childhood. It is an inspirational feeling. Beyond the great art museums of the world, some of my favorites include medical museums and museums of natural history.

(...)

In the same spirit as those earlier collectors filling their cabinets of curiosities, I feel compelled to collect quite a variety of things. I draw artistic inspiration from the treasures I find at the flea market. I like old toys, books, photographs, anatomical models, stuffed animals, skeletons, religious statues, and vintage paper ephemera. It is interesting how, from the endless sea of stuff out there, certain things jump out. They evoke a feeling of mystery in me and I am powerfully driven toward them. It is an obsession. I collect, arrange, and display them. Pieces from my collection end up synthesized or juxtaposed in my paintings.

This visual debris from contemporary pop culture contains the specific archetypes that formed my consciousness while living in this particular period in history. I often find archetypes in old children’s books and toys, so these things make up a large part of my collection. I am attracted to things that evoke memories from childhood.

It is only in childhood that contemporary society truly allows for imagination. Children can see a world ensouled, where bunnies weep and bees have secrets, where “inanimate” objects are alive. Many people think that childhood’s world of imagination is silly, unworthy of serious consideration, something to be outgrown. Modern thinking demands that an imaginative connection to nature needs to be overcome by “mature” ways of thinking about the world. Human beings used to connect to life through mystery and mythology. Now this kind of thinking is regarded as primitive or naive. Without it, we cut ourselves off from the life force, the world soul, and we are empty and starving.

I believe in letting imagination thrive in my art. I am not afraid of nostalgia or sentiment. I value taking the time to make a painting “beautiful.” I want to breath life into my paintings.

(...)"